Day 1

Habits of Mind: Critical Thinking and Defining World History from Global Perspectives

I. Habits of Mind: interpreting South East Asian architecture

II. Supra-National Themes: ideas we bring to our teaching

III. Why we do this: organizing themes and rationale

IV. Teaching Locally and Learning Globally: potential and contradictions

V. Process writing: the history journal/notebook

VI. Maps for Illustrating Global Themes

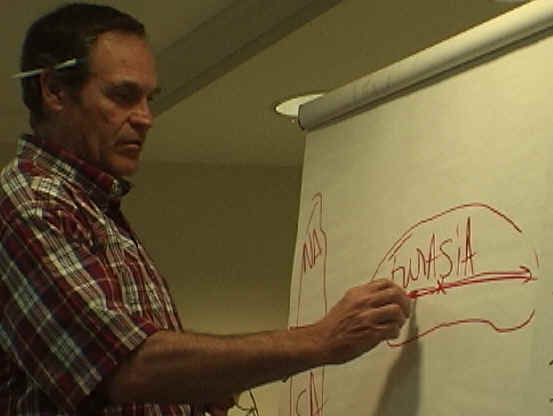

I. Habits of Mind: interpreting South East Asian architecture

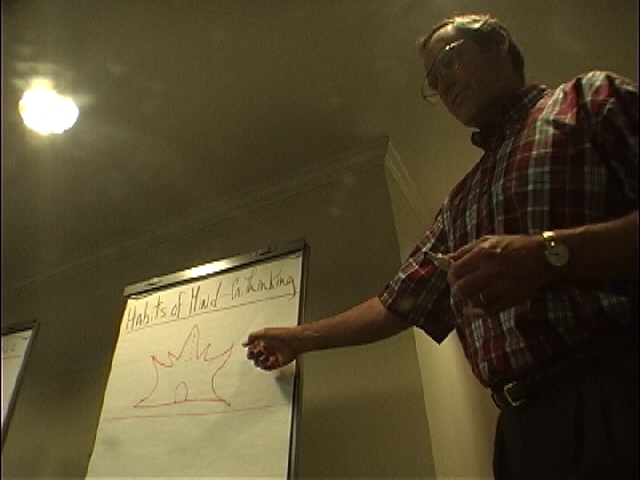

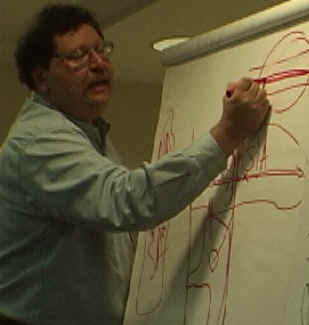

In

the first eight hours of the workshop, a recurrent question arose: How do we

conceptualize and/or do not conceptualize materials and methods in our teaching

of world history. We can begin to conceptualize world history for ourselves

and our students by using relevant content with the broadest significance. This

approach is also the only way to begin to manage an otherwise daunting volume of

world history. Professor Marc Jason Gilbert, the institute's leading world

historian, explains how even a simple sketch of a SE Asian Buddhist or Hindu

temple can represent broad themes in our studies and teaching of world history,

thus making our teaching of world history more manageable. The sketch of South

East Asian architecture represents the mixing and fusion of many influences

permeating Buddhism and Hinduism in South East Asia. The participants would soon

reveal that the theme of religious transformation is among their favorites in

world history. Referring to the sketch, Professor Gilbert contended that

students' explorations of temple architecture in Asia should at least lead them

to see that there are symbols other than the cross that people hold sacred.

Such syncretic architecture in SE Asia in the first millennium C.E. can even be

compared to developments in the Christian world as it spread in the second

millennium throughout Europe and the rest of the world.

In

the first eight hours of the workshop, a recurrent question arose: How do we

conceptualize and/or do not conceptualize materials and methods in our teaching

of world history. We can begin to conceptualize world history for ourselves

and our students by using relevant content with the broadest significance. This

approach is also the only way to begin to manage an otherwise daunting volume of

world history. Professor Marc Jason Gilbert, the institute's leading world

historian, explains how even a simple sketch of a SE Asian Buddhist or Hindu

temple can represent broad themes in our studies and teaching of world history,

thus making our teaching of world history more manageable. The sketch of South

East Asian architecture represents the mixing and fusion of many influences

permeating Buddhism and Hinduism in South East Asia. The participants would soon

reveal that the theme of religious transformation is among their favorites in

world history. Referring to the sketch, Professor Gilbert contended that

students' explorations of temple architecture in Asia should at least lead them

to see that there are symbols other than the cross that people hold sacred.

Such syncretic architecture in SE Asia in the first millennium C.E. can even be

compared to developments in the Christian world as it spread in the second

millennium throughout Europe and the rest of the world.

Tom Mounkhall, our veteran secondary school teacher from New York state, assures the participants that the new content and themes in the AP certified course will require teachers to push students' critical thinking to new levels. It is the teacher's responsibility to enable advanced students to think critically from a variety of perspectives. Cultural diffusion should become an obvious theme analyzing art and architecture. Here are the Habits of Mind acknowledged by the College Board as of 2001 (notice the big difference between the first and the second set of skills):

Habits of Mind or Skills

The AP World History course addresses habits of mind or skills in two categories:

1) those addressed by any rigorous history course,

2) those addressed by a world history course.

Four Habits of Mind are in the first category:

1a. Constructing and evaluating arguments: using evidence to make plausible arguments.

1b. Using documents and other primary data: developing the skills necessary to analyze point of view, context, and bias, and to understand and interpret information.

1c. Developing the ability to assess issues of change and continuity over time.

1d. Enhancing the capacity to handle diversity of interpretations through analysis of context, bias, and frame of reference.Three Habits of Mind are in the second category:

2a. Seeing global patterns over time and space while also acquiring the ability to connect local developments to global ones and to move through levels of generalizations from the global to the particular.

2b. Developing the ability to compare within and among societies, including comparing societies’ reactions to global processes.

2c. Developing the ability to assess claims of universal standards yet remaining aware of human commonalities and differences; putting culturally diverse ideas and values in historical context, not suspending judgment but developing understanding.

Several teachers claim that they will test their students on these habits of mind early in the course to make sure they first memorize them so that they can more readily them as the course progresses.

II. Supra-National Themes: ideas we bring to our teaching

The participants are asked to identify additional supra-national themes in world history that they would like to develop further. Supra-national themes of course require thinking using world historical, or global perspectives.

|

|

|

|

Kirby |

Marion |

Brian |

Similarities of organized religion, Religion and ethics, Institutions of government and law, the theory and practice of war and peace, migration and diffusion.

|

|

|

|

Faith |

Gary |

David |

Spread of religions, social changes and the role of women, marginalization of social groups, civilizations, modern life, "man's place in the world," migration patterns, transformation of religions, cross-cultural exchange, language developments

Marc notes that part of the Jews' inflexibility regarding Jerusalem is their collective memory of being forced out of Jerusalem by Christian groups through the centuries.

|

|

|

|

Barbara |

Maureen |

Kathryn |

Cross cultural contact and cultural diffusion, conflict, religion, government, the environment, and individual choices.

Participants conclude that students' explorations of cross-cultural contact should be sophisticated, and our approach multi-dimensional. Ninth, tenth, and eleventh graders' minds should be ready for complex answers. Julie notes that younger children are increasingly able to manipulate complex ideas and we conclude that students use of computers should also increase their analytic capacity.

|

|

|

|

Julie |

John |

Patrick |

Cultural complexity and gender, connectivity between ancient civilizations and modern practices in different parts of the world (democracy in Rome versus democracy in America), comparative empires and imperialism, and patriotism and religion, trade openness and trade isolation.

Tom introduces the first of many "teaching gems" we would discover throughout the institute. To get students to think more analytically about civilizations across the ages, he asks this kind of question: Which century would 18th century Americans be comfortable in: the nineteenth century? or the first or second century?; Why?

|

|

|

|

Gordon |

Beverly |

Dave |

The impact of technology on different societies, trade alliances, belief systems and religion, assimilation reflected through art and music. (Marc notes that students using art and music is effective not only as a subject, but a technique, since it has been proven that children remember more through audio and visual aids.) Intellectual and cultural interactions, why some ideas find fertile ground and some do not.

Tom recommends an important book on the modern history of technology by Daniel Headrick, The Tools of Empire.

|

|

|

|

Mary |

Steve |

Martha |

What if the Moslems had sailed to the Americas in 1492?, interactions of geography and culture, race (overcoming racial prejudices, or the black/white paradigm, in a South Carolina school, trusting movies more than books), comparing cross-culturally, the impact of ideas

|

|

|

Mary Anne |

Steven |

The fact that our views of the world are unique no matter how wide a study we strife, comparing empire and parochialism, conflict versus consensus, food and disease, cultural diffusion, "connecting the dots," conduits of exchange, the achievements of all peoples.

General reflections on the comments:

Human Rights -- Marion wonders from when and where did the first examples of racism based on color derive. Wasn't it the Portuguese? The group responds that marginalization and racism, has a multitude of origins. Indeed, the theme of human rights with its long history -- especially since the French Revolution -- becomes an important theme many teachers emphasize especially in the period since 1914.

Causation in History -- Tom reminds the group that causation and history are often viewed synonymously; but that today's historians seek multiple causes. From a multi-dimensional approach, technology can even be seen as a cause of imperialism. Going back in history, technology could be viewed as a cause of the rise of Emperor Ch'in and the founding of the first dynasty of China. Marc concludes that students should draw their own conclusions regarding causation or various types of determinism.

III. Why do we do this: organizing themes and rationale

A final rhetorical question for the group before lunch: "Why do we do this?!"

Is it -- to prevent the recurrence of war; to develop understanding of world trade relationships, man's relationship to the environment (i.e. disease, plague, Columbian Exchange, Harappan and Mayan deforestation); weapons development in the context of military history, technology sharing and diffusion, migration, synthesis, homogeneity (Japan as an exception), to understand gender in history?

Gender -- The theme of gender arose only once among the participants' initial introductions, so Tom and Marc remind us that there are many fascinating cases in which women prove to be a deciding factor in historical change. The case of Cortez's interpreter, Modona Melinche (a good friend of Cortez's son), is a popular one. Marc recommends a book called Between Worlds.

Is it? -- to understand littorals (exchange basins like the Indian Ocean, bananas from Madagascar, why Arabic numbers are similar to Sanskit script?

Certainly potential reasons for 'doing' world history are endless and they should be. If there is anything that we can conclude from our first attempt to define world history, it is that every teacher should emphasize the themes that he or she feels to be important. The A.P. guidelines should not be seen as a bible, but should be interpreted broadly to integrate the personal interests of both the students and teachers.

After

lunch, Tom holds up a box to emphasize a thematic approach to history versus a

content-based approach. In all practicality, teachers will need to choose

several effective themes to help organize the content of the course. McNeill and

Bentley use Political, Economic, Ecological, and Social themes to make global

connections. Whatever themes you choose, they will need to be reinforced

constantly. Marc adds that other themes like Gender, Technology, and Trade work

as well. On the next level, over-riding objectives to help organize your themes

might also help develop the course. Marc says that William McNiell's over-riding

objective appears to be to make us less prone toward war. Other world historians

seek to stamp out racism and replace it with true cross-cultural understanding.

Teaching in the South, many of the participants say that they can relate to that

objective.

After

lunch, Tom holds up a box to emphasize a thematic approach to history versus a

content-based approach. In all practicality, teachers will need to choose

several effective themes to help organize the content of the course. McNeill and

Bentley use Political, Economic, Ecological, and Social themes to make global

connections. Whatever themes you choose, they will need to be reinforced

constantly. Marc adds that other themes like Gender, Technology, and Trade work

as well. On the next level, over-riding objectives to help organize your themes

might also help develop the course. Marc says that William McNiell's over-riding

objective appears to be to make us less prone toward war. Other world historians

seek to stamp out racism and replace it with true cross-cultural understanding.

Teaching in the South, many of the participants say that they can relate to that

objective.

IV. "Teaching Locally and Learning Globally": potential and contradictions

Julie says that her world history class at least potentially helps solve some of the Latino/Anglo tensions at her school by giving the students a more global perspective. Marc responds that when you teach world history through local examples and connections, students learn globally more efficiently. Mary Anne mentions that she teaches about the Reformation through examples of Huguenots and Anabaptism in Georgia history.

Ed reminds us, however, that because of the high percentage of students who are not originally from the locality, using local referents may not always work. Furthermore, often local symbols represent the perennial tension between the local and the global (foreign or Other). Many local examples of hangings, etc. reflect early reactions against globalism. Tom Watson's Agrarian Culturalism expands on this thesis.

On a more positive note, Mary adds that there is a strong Asian presence in her school and a world history may be an answer to there requests for an Asian Studies program. Marion wonders if world history courses would help neutralize or aggravate the militia-type students whose parents fear a world government. Many students still relate to the old adage that war is the ultimate test of courage, and therefore a good thing. Marc responds that there are enough examples in world history that students should begin to see that parochialism is a cost to progress. Let the results of violence and war speak the lesson. Tom responds that building our global identity on top of our national identity is a good thing. He recommends the movie Peloponnesian War.

V. Process Writing: the history journal/notebook

The day concludes with a pep talk for introducing history journals to our own and our students' studies . Because writing is thinking, the only way that we can begin to understand our 'habits of mind' is to write and reflect on our thoughts -- in more technical terms, construct and deconstruct them. We have the intellectual luxury of reflection. Share it, keep it to yourself, it is your journal.

Here's a sample journal/notebook form that Tom recommends:

| The Facts (notes and data from class, the text, and source readings) | Personal reflections (disagreements over pedagogy, linkages to abstract concepts over time and space, personal experiences, sub-texts, sub-plots, global themes, etc.) |

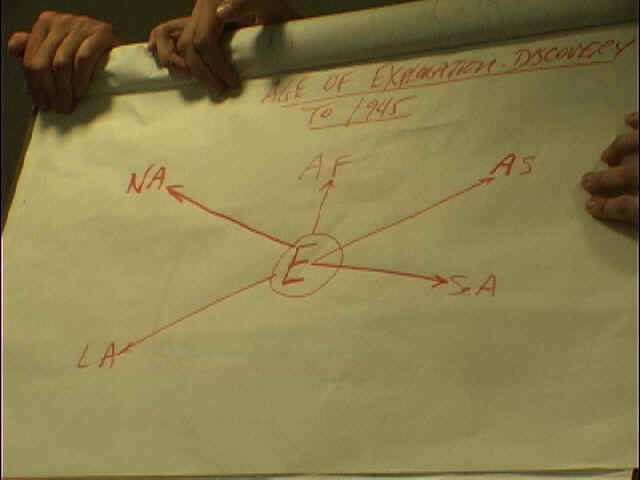

VI. Maps for Illustrating Global Themes

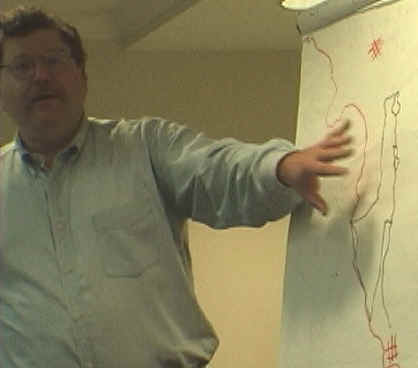

Introducing

mapping exercises that give students a more global view of the world, Tom

recalls a workshop in New York given by an a prominent Imam. The Imam, while

discussing the five pillars of Islam, pointed to the corner of the room when as

he explained what direction they face when they pray to Mecca five times a day.

This reference baffled many of the teachers attending and after the

presentation, Tom, asked the Imam why he pointed in that direction. The Imam

responded that that is the direction in which they fly home from New York. The

Imam's orientation was clearly global and necessarily so. Instead of relating to

Mecca in an abstract way through a map or even a globe, the Imam oriented

himself globally five times a day at prayer time. The point is -- teachers need

to make global themes in as relevant a manner possible. There are many ways to

construct a more global geography in students' minds. Tom says that in his

class, he changes the class's view of the globe every day. One day its

Antarctica, another day its Siberia.

Introducing

mapping exercises that give students a more global view of the world, Tom

recalls a workshop in New York given by an a prominent Imam. The Imam, while

discussing the five pillars of Islam, pointed to the corner of the room when as

he explained what direction they face when they pray to Mecca five times a day.

This reference baffled many of the teachers attending and after the

presentation, Tom, asked the Imam why he pointed in that direction. The Imam

responded that that is the direction in which they fly home from New York. The

Imam's orientation was clearly global and necessarily so. Instead of relating to

Mecca in an abstract way through a map or even a globe, the Imam oriented

himself globally five times a day at prayer time. The point is -- teachers need

to make global themes in as relevant a manner possible. There are many ways to

construct a more global geography in students' minds. Tom says that in his

class, he changes the class's view of the globe every day. One day its

Antarctica, another day its Siberia.

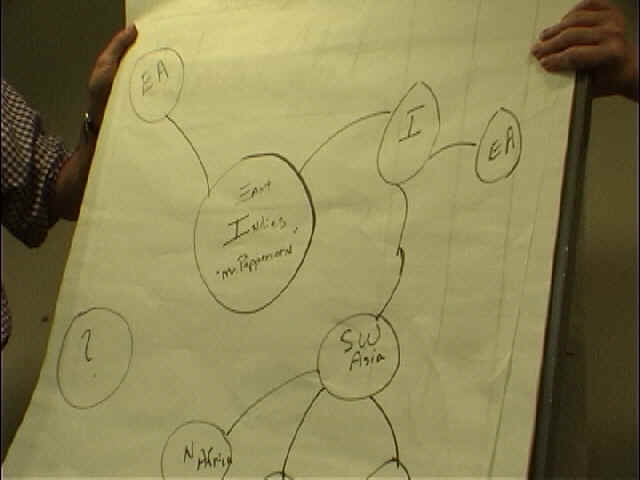

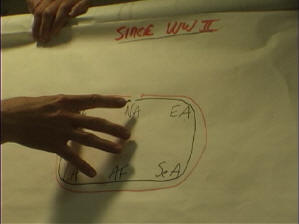

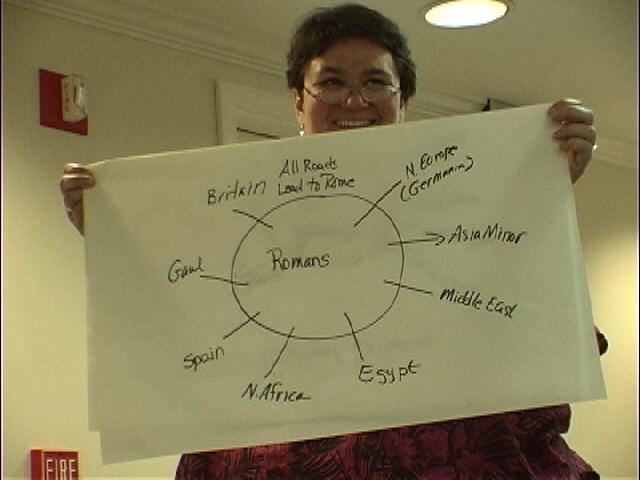

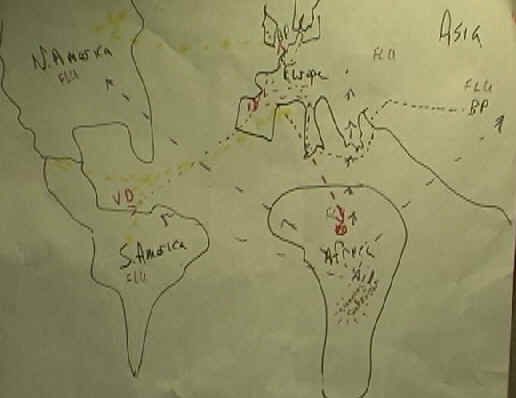

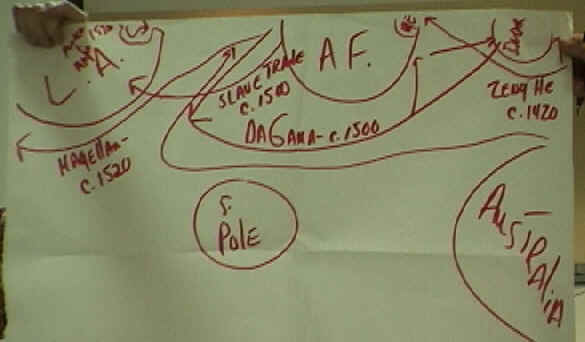

Maps should emphasize connections. There is no ideal map for teaching world history only particular maps for particular teaching functions. The participants break down into groups to come up with some unique maps for particular teaching functions.

A few map ideas from the group (organized according to chronology:

|

|

|

"Mr. Peppercorn travels" |

Age of Exploration/Discovery to 1945 contrasts with the global age (the directions of trade are not as clear as they were once) |

|

|

|

|

All Roads Lead to Rome |

Diseases: What are the differences in the way these diseases (VD, BP, Flu, Sleeping Sickness, Small Pox, etc) expand and why? |

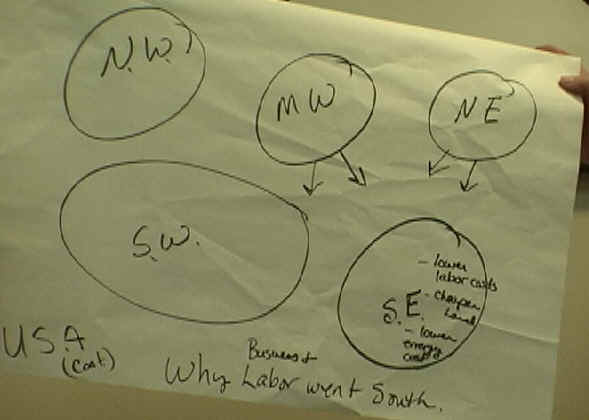

Why labor went south |

|

|

|

|

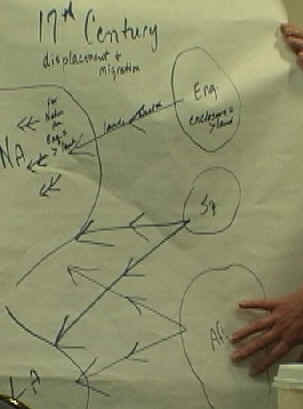

Displacement and Migration: the push and pull factors involved in the 17th century |

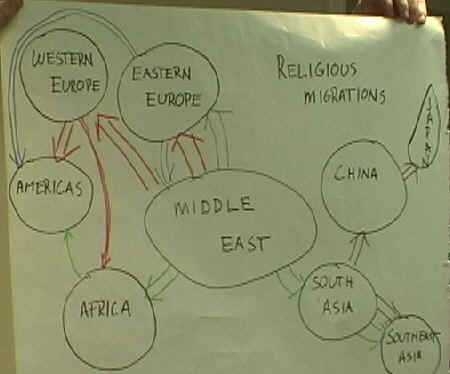

Migration and Diffusion of Religion (Red is Christianity and Green is Islam) Tom recommends students taking this map home and redoing it from the perspective of a Hindu. How would the relative size of the regions change? |

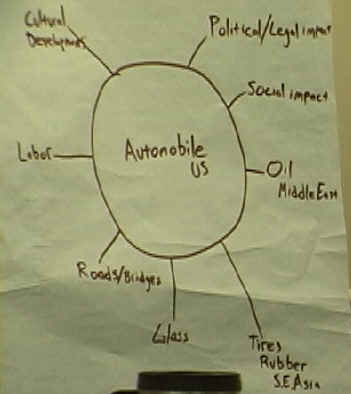

Influence of technology (tires and rubber from SE Asia, glass, Venetians' and Romans' early contributions, etc. |

|

|

|

|

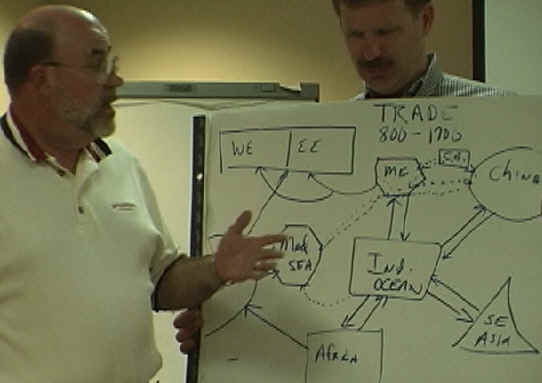

Trade between 800 and 1750 emphasizing the Indian Ocean Littoral |

Israel, emphasizing the close nature of the conflicts with Syria and Lebanon |

From a different perspective, oceans can be seen as the connectors, exploration was only done by Western Europeans |

|

|

|

Tom compares the relative trade benefits of common lines of latitude in Eurasia versus the wider range in N. and S. America |

Marc argues that vertical integration of Africa is as significant as the horizontal; he also illustrates the once common theory that environmental conditions are more favorable along the forty degree lines of latitude. |

Through our discussions on interpreting South East Asian architecture, ideas we bring to our teaching, and organizing themes for the course, we can conclude that there is no one rationale that historians can or should agree on for their teaching, but in the Southern United States where most of the participants are employed, giving more exposure to a variety of social groups in a more global context is the the predominant rationale. Through our exercise in world map-making, we illustrated global topics like trade and migratory paths, the diffusion of technology, and the transformation of religion. Such habits of mind lead toward an increased understanding of the significance of all peoples in human history in contrast to most 19th and 20th century approaches that sought to justify the dominance of a few European peoples. A more global approach to world history also reveals that peoples' common struggle with the environment have linked peoples through trade during longer periods than conflict and war has separated them. Yet, our habits of thinking about the world, especially at the local level, often remain entrenched in former narrowly definitions of world history. Such tendencies contradict the possibilities of even appreciating global influences at the local level. In the southeastern U.S., this is especially true. Teachers in the Southeast, therefore, often agree on the rationale for world history to instill more global perspectives and diminish 19th century racial attitudes. But outside and inside the framework laid-out in the A.P. guidelines teachers' preferences for course design and teaching methods show a wider variety of opinion as the institute progressed.

References cited: